You’ve probably seen it happen. A walkway that looked solid a few years ago now dips in the middle, tilts after heavy rain, or turns slick with ice every winter. In St. Louis, those problems aren’t random. They’re a predictable response to what’s happening under and around the surface.

Walkway failure refers to the sinking, cracking, shifting, or erosion of a walkway caused by soil movement, water mismanagement, slope forces, and freeze–thaw stress. In the St. Louis area, expansive clay soil, heavy spring rainfall, and repeated freeze–thaw cycles combine to put constant pressure on walkways that weren’t built with those conditions in mind. Add sloped yards and poor drainage, and even newer installations can start failing sooner than expected.

This guide breaks down why walkways fail in St. Louis at a system level. You’ll learn how clay soil behaves, how water moves across and under walkways, how slope changes everything, and what proper walkway installation needs to account for in this region so problems don’t keep coming back.

What’s Really Causing Walkway Problems in St. Louis

Here’s the thing most homeowners don’t realize until they’re dealing with repairs. When a walkway starts dipping, cracking, or washing out, the damage usually began years earlier, below the surface. If you’ve ever noticed a low spot forming near a downspout or ice building up on one section every winter, you’ve already seen these forces at work.

-

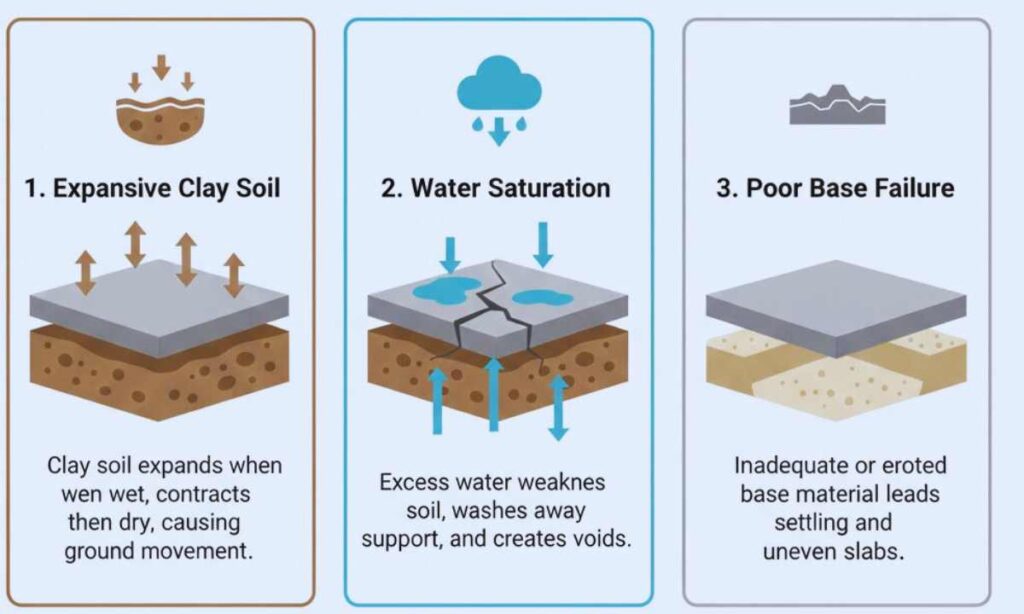

Clay soil movement

St. Louis sits on expansive clay soil, which swells when it gets wet and shrinks as it dries. That constant push and pull shifts whatever sits on top of it. If the soil beneath a walkway wasn’t prepared to handle that movement, the surface above it will eventually follow. -

Water saturation and erosion

Water is the main trigger. Heavy spring rains, roof runoff, or water flowing across a sloped yard can saturate the soil and slowly wash support away. Over time, that erosion creates empty pockets under the walkway, leading to sinking sections or edges that wash out after storms. -

Base failure below the surface

Many walkways fail because the base layer wasn’t built deep enough or compacted properly. Once the base loses strength, surface fixes become temporary at best. This is why resetting stones or patching concrete often looks fine at first but doesn’t hold up through another wet season. -

Material performance depends on the system

Concrete, pavers, and gravel all behave differently in St. Louis conditions, but none of them can overcome poor soil prep or drainage. When a walkway fails, the material usually gets blamed even though the real problem is the system underneath it.

What that means for you is simple. If a walkway keeps cracking, sinking, or washing out, stop chasing surface repairs. The lasting fix comes from addressing the soil, water, and base together, the same forces that caused the problem in the first place.

The Fast Answer: Why Walkways Fail in St. Louis

Walkways fail in St. Louis for one simple reason: the ground underneath them never stays still. Expansive clay soil moves as moisture changes, water exploits weak spots, and freeze–thaw cycles magnify small installation mistakes. A walkway can look fine for years, then start failing once those forces finally catch up.

Is St. Louis Especially Hard on Walkways?

Yes. St. Louis puts more stress on walkways than many homeowners expect.

Much of the area sits on expansive clay soil. When it gets wet, it swells. When it dries, it shrinks. Layer in heavy spring rain and winter freeze–thaw cycles, and the ground is constantly shifting beneath the surface. If a walkway wasn’t built to handle that movement, problems are almost inevitable.

That’s why failures often show up later, not right away. The walkway didn’t suddenly fail. The soil finally moved enough to expose the weakness.

What Walkway Failure Looks Like in Real Homes

It usually shows up as uneven surfaces and water-related damage. These signs tend to appear gradually, then accelerate once the base loses support.

Common warning signs include:

-

Sinking sections where soil has compressed or washed out underneath, often near downspouts or low spots where water collects.

-

Heaving or raised edges caused by freeze–thaw pressure lifting parts of the walkway during winter.

-

Cracking or separating joints when rigid surfaces can’t flex with soil movement.

-

Washouts along edges after heavy rain, where runoff erodes the base.

-

Pooling water that lingers after storms and turns into ice patches in winter.

If you’re seeing one of these issues, the others usually aren’t far behind. They’re all driven by the same forces below the surface, which is why lasting fixes start there, not on top of the walkway.

How to Identify Why Your Walkway Is Failing (Fast Diagnosis)

Most walkway problems leave clear clues if you know how to read them. The surface issue you’re seeing usually points straight to what’s happening underneath. This section helps you connect the symptom to the cause so you can stop guessing and focus on what actually needs to be fixed.

If Your Walkway Sinks After Rain, Start Here

Yes, sinking after rain almost always means water is weakening the soil or base below. When clay soil stays saturated, it loses strength and compresses under weight.

You’ll often notice this within a day or two after a heavy storm. A section feels lower than it did before, especially near downspouts or natural low points in the yard. That’s water soaking into the soil and slowly washing support away.

Two conditions usually drive this:

-

Saturated clay soil that swells when wet, then softens as moisture lingers.

-

Erosion beneath the base, where moving water quietly removes material over time.

If the walkway drops a little more after each storm, the problem isn’t settling on its own. It’s ongoing water exposure.

If Your Walkway Heaves or Lifts in Winter, Start Here

Yes, winter lifting is typically caused by frost heave from trapped moisture. This can happen even without heavy foot traffic.

Here’s what’s going on. Water trapped in the soil freezes during cold snaps and expands. Clay soil holds moisture longer, so the expansion pushes parts of the walkway upward. The lift is rarely even, which is why new trip points often appear overnight in winter.

Pay attention to the pattern:

-

If sections rise in winter and settle back down in spring, moisture and freezing are the driving forces.

-

If the lifting happens in the same spots each year, the water source hasn’t been addressed.

Surface repairs won’t stop this until the moisture problem is resolved.

If Your Walkway Washes Out During Storms, Start Here

Yes, washouts usually mean runoff is being funneled toward the walkway and the edges can’t hold it. This is common on sloped lots or where water crosses the path during storms.

You might see soil exposed, gravel disappearing, or pavers losing support along the edges right after heavy rain. That’s runoff cutting into the base and carrying material away.

The usual culprits are:

-

Concentrated runoff from slopes, driveways, or roof drainage.

-

Weak or missing edge restraint that allows material to spread and wash out.

If damage worsens after every storm, the water path has to be redirected before any repair will last.

If Cracks or Gaps Keep Reappearing, Start Here

Yes, recurring cracks or gaps point to subgrade movement or poor compaction. When the ground beneath keeps shifting, surface fixes don’t stand a chance.

This shows up as cracks reopening in the same spots or joints that separate again after being reset. You might also notice the gaps widen after wet periods and tighten during dry weather.

That pattern tells you the soil underneath is still moving. Until the subgrade is stabilized and the base rebuilt correctly, repairs will keep failing no matter how often they’re touched up.

Recognizing these patterns early makes the next step clearer. Once you know whether water, freezing, or soil movement is driving the damage, you can address the root cause instead of chasing symptoms.

The St. Louis Walkway Failure Triangle

If a walkway fails in St. Louis, it’s almost never one single mistake. It’s clay soil reacting to water on a slope. Those three forces work together, slowly stressing the ground until the surface finally gives way. Once you understand how that triangle works, the failures stop feeling random and start making sense.

Clay Soil Movement: Why the Ground Won’t Stay Put

Yes, expansive clay soil is a primary reason walkways fail in St. Louis. Clay expands when it absorbs moisture and shrinks as it dries, and that movement never really stops.

Here’s what catches homeowners off guard. Clay doesn’t fail fast. It shifts gradually through seasonal wet and dry cycles. A walkway can look fine for a year or two, then start dipping or cracking once the soil has moved enough to stress the base. That it looked fine at first pattern is a classic sign of clay-driven failure.

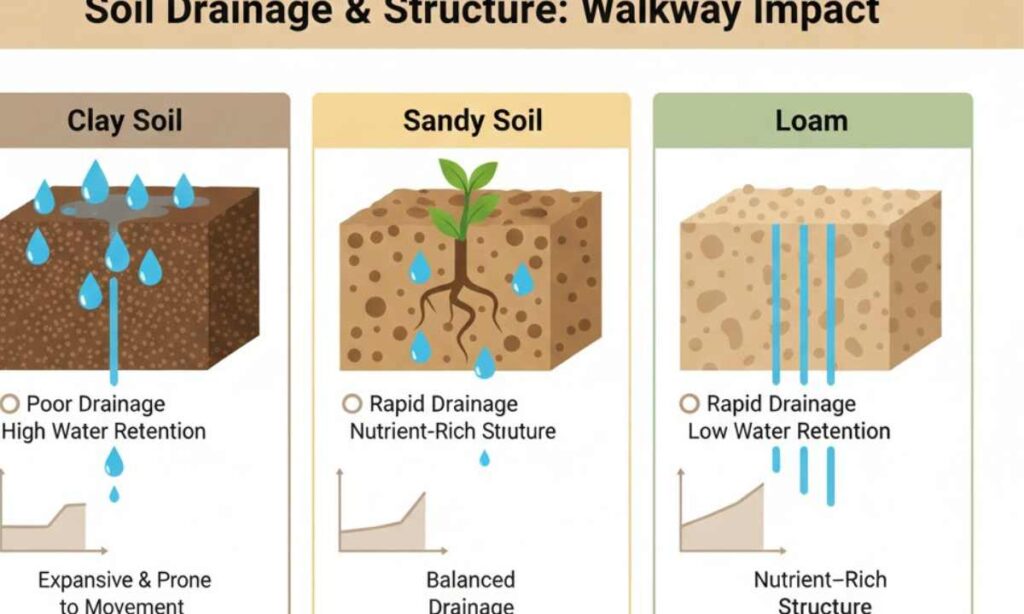

What Makes Clay Soil Different From Sandy or Loamy Soil?

Clay soil holds water and changes shape far more than sandy or loamy soil. That difference is what makes it so hard on walkways.

Sandy soil drains quickly and stays relatively stable. Loamy soil balances drainage and structure. Clay does the opposite. It traps moisture, swells under load, and releases water slowly. Over time, that constant expansion and contraction puts steady pressure on rigid surfaces like walkways.

This behavior is well documented in regional soil studies and extension research.

Trusted resource to reference: USDA Soil Survey or a University Extension guide on expansive clay soils.

Signs Clay Soil Is the Main Culprit

Yes, clay soil leaves clear, repeatable clues. These signs usually come and go with the seasons rather than foot traffic.

Homeowners often notice:

-

Gaps forming along edges during dry periods as soil shrinks away.

-

Seasonal cracking that opens in drought and tightens after heavy rain.

-

Low spots that keep coming back, even after being filled or leveled.

If the changes track with weather patterns instead of use, clay movement is likely driving the damage.

Drainage and Water: The Hidden Force Under Every Failure

Yes, water is what turns soil movement into visible damage. Clay alone causes stress, but water is what accelerates failure.

Think about a spring thunderstorm that dumps rain faster than the yard can absorb it. Water pools, runs along the walkway, or soaks straight into the soil beneath. Once that soil stays wet, it weakens, swells, and becomes vulnerable to erosion. In St. Louis, repeated spring rain makes this cycle hard to avoid without proper drainage.

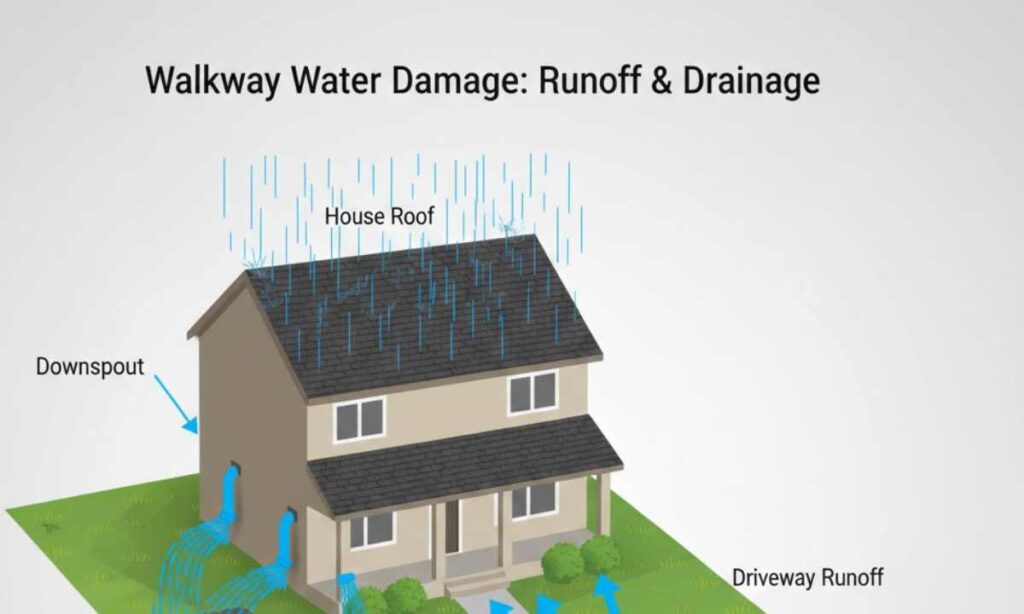

Where the Water Usually Comes From in Real Homes

Most walkway water problems come from everyday features that seem harmless. It’s rarely a single storm. It’s repeated exposure.

Common sources include:

-

Downspouts that discharge too close to the walkway.

-

Driveway runoff that naturally flows downhill.

-

Sloped yards that send water across the path during rain.

-

Gutter overflow during heavy storms.

Why Water Causes Both Sinking and Heaving

Yes, the same water issue can cause opposite failures depending on the season.

In warm months, saturated soil loses strength and erodes, leading to sinking and settlement. In winter, that same trapped moisture freezes and expands, lifting sections of the walkway. That’s why some walkways dip in summer and heave in winter even though the underlying cause hasn’t changed.

Slope and Grading: How Small Pitch Mistakes Destroy Walkways

Yes, grading errors that look minor can cause major problems. Many walkways appear flat to the eye but still direct water the wrong way.

A slope that feels barely noticeable underfoot can turn a walkway into a water channel or a dam that traps moisture. Over time, that constant flow or pooling erodes the base and shifts the surface, even though nothing looks obviously wrong at first.

The Two Slope Problems Homeowners Don’t Notice Until It’s Too Late

Yes, slope-related damage accelerates once erosion starts. By the time it’s obvious, the base is often already compromised.

Two patterns show up most often:

-

Channelized flow, where water runs along the walkway like a shallow gutter.

-

Cross-cutting runoff, where water repeatedly slices across the surface and undermines edges.

Once either pattern sets in, damage speeds up quickly. That’s why clay soil, water, and slope have to be handled together. Ignoring any one of them almost guarantees the others will cause trouble later. Most walkway water problems come from everyday features that don’t seem related until the damage keeps repeating. Downspouts dumping too close to the path, gutter overflow during heavy storms, and slope flow crossing the walkway all add moisture where it doesn’t belong. Driveways are a common trigger, they shed water fast, and that runoff often heads straight toward walkways. In those cases, the long-term fix usually starts by addressing how the driveway itself is designed to handle runoff, not just repairing the path it damages.

Is Walkway Failure in St. Louis Inevitable or a Sign of Poor Installation?

This is where most homeowners start second-guessing everything. If walkways fail so often in St. Louis, is that just the cost of living here, or did something go wrong during installation? The honest answer is this: St. Louis is hard on walkways, but failure is not inevitable. When problems show up early or keep coming back, installation decisions are usually part of the story.

What Even Good Installations Must Account For in St. Louis

No, walkway failure is not inevitable when the installation is designed for St. Louis conditions. But good installation here means more than neat lines and solid materials.

A proper installation assumes the soil will move. Expansive clay is going to swell and shrink. Heavy rain will find low spots. Slopes will redirect water whether anyone planned for it or not. Good installations don’t try to lock the walkway in place and hope for the best. They manage movement, control water, and shape the surface so gravity works in their favor.

In practical terms, that means building a base that can flex slightly without collapsing, giving water a path away from the walkway instead of underneath it, and grading the surface so runoff never lingers where it can do damage. When those factors are handled upfront, walkways hold up far longer in St. Louis conditions.

Red Flags That Point to Installation Shortcuts

Yes, many walkway failures trace back to shortcuts taken during installation. These issues often stay hidden until moisture and seasonal changes expose them.

Here are the warning signs that usually point to deeper problems:

-

Thin base layers that can’t support shifting clay soil, leading to settling after rain.

-

Poor compaction that allows the base to collapse once it gets wet.

-

Missing or ineffective drainage, which lets water sit where it weakens the soil.

-

No edge restraint, allowing materials to spread, sink, or wash out over time.

These shortcuts don’t always cause immediate failure. That’s why a walkway can look fine at first and still fall apart a few seasons later. If several of these signs are present, the issue isn’t bad luck or bad weather. It’s a system that was never built to handle St. Louis reality.

The key takeaway is this. Local conditions don’t doom a walkway on their own. When failures keep happening, it’s usually because the installation didn’t fully account for how soil, water, and slope behave here. Once you know what to look for, the difference between inevitable damage and preventable failure becomes much clearer.

How Long Walkways Should Last in St. Louis Conditions

Homeowners usually ask this right after something fails: how long was this supposed to last? The answer depends less on the surface material and more on whether the installation accounted for St. Louis soil, water, and winter stress. When those factors are handled correctly, walkways can last decades here. When they aren’t, lifespan drops fast.

Expected Lifespan by Walkway Material (When Installed Correctly)

Yes, walkways can last a long time in St. Louis when they’re built for local conditions. The material matters, but only as part of the overall system.

Here’s what homeowners can realistically expect:

-

Concrete walkways

When properly installed with a stable base and good drainage, concrete walkways often last 20 to 30 years in this region. Problems usually show up sooner when water gets under the slab or freeze–thaw cycles stress weak spots. -

Paver walkways

Interlocking pavers typically last 25 to 50 years or more when the base is built correctly. Because pavers can flex slightly with soil movement, they tend to handle clay and freeze–thaw cycles better than rigid slabs. -

Gravel walkways

Gravel has the shortest lifespan, usually 10 to 20 years, and requires regular maintenance. It performs best where drainage is excellent and slopes are minimal.

These timelines assume proper soil preparation, compaction, drainage, and grading. Without that groundwork, even the best material won’t reach its expected lifespan.

What Shortens Walkway Lifespan the Most in St. Louis

Yes, most premature failures come from the same repeat issues. In St. Louis, environment matters more than foot traffic.

The biggest lifespan killers are:

-

Ongoing water exposure, which weakens the base and accelerates erosion.

-

Soil movement from expansive clay, causing settlement in summer and stress during dry periods.

-

Freeze–thaw stress, where trapped moisture expands in winter and shifts the surface.

What that means is simple. A walkway doesn’t fail early because someone used it too much. It fails because water, soil, and temperature changes weren’t managed together. When those forces are controlled from the start, walkways in St. Louis can meet or exceed their expected lifespan instead of falling short.

Materials and How They Perform Under St. Louis Conditions

Here’s the straight truth. In St. Louis, materials don’t fail because they’re bad. They fail when they’re expected to solve soil, water, and slope problems they weren’t designed to handle. Once you look at materials through that lens, their performance here makes a lot more sense.

Is Gravel a Good Walkway Choice in St. Louis?

Sometimes, but it comes with real tradeoffs. Gravel can work in limited situations, but it’s unforgiving when conditions aren’t right.

You’ve probably seen this play out. After a heavy rain, gravel paths turn muddy, material drifts into the lawn, and low spots start forming where people walk most. That happens because water moves straight through the gravel and softens the clay below. Without strong edging, the gravel has nothing holding it in place.

Gravel performs best on flat ground with excellent drainage, solid edge restraint, and a well-prepared base. Without those controls, maintenance becomes constant rather than occasional.

Can Concrete Handle St. Louis Freeze–Thaw Cycles?

Yes, but only when the ground underneath is built correctly. Concrete is strong, but strength doesn’t help when the ground moves.

Concrete’s rigidity is both its advantage and its weakness. When clay soil expands, contracts, or freezes under a slab, the concrete can’t flex to absorb that movement. If water gets trapped below and freezes, the pressure has nowhere to go, which leads to cracking or heaving.

Most concrete failures in St. Louis aren’t surface issues. They’re subgrade problems. When concrete is placed over a deep, well-compacted base with proper drainage, it can last decades. When it isn’t, freeze–thaw cycles expose weaknesses quickly.

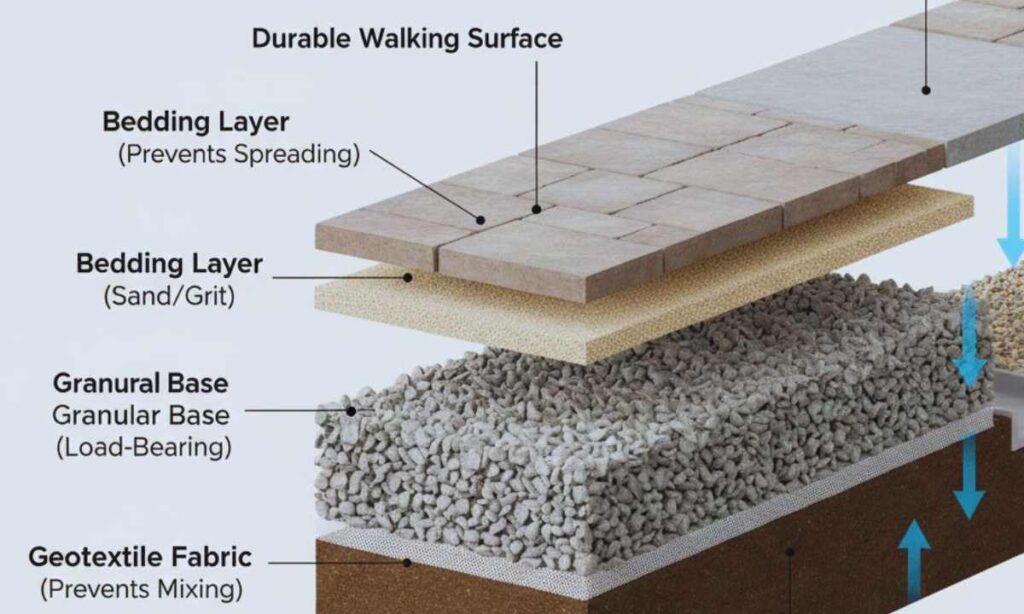

Why Pavers Often Perform Better on Clay Soil

Because they can move without breaking. That flexibility gives pavers a real advantage on expansive clay.

Interlocking pavers sit on a compacted base and sand layer that allow slight movement as the soil shifts. Instead of cracking, the surface adjusts and settles back. Water can move through joints and along the base instead of pooling under one rigid slab.

There’s also a practical benefit homeowners appreciate later. If a section settles, individual pavers can be reset without tearing out the entire walkway. That modular repairability aligns well with how clay soil behaves over time.

When Pavers Still Fail (And Why)

Yes, pavers still fail when the system underneath is compromised. Flexibility doesn’t fix shortcuts.

Failures usually come back to:

-

Insufficient base depth, which can’t support shifting clay.

-

Poor compaction, allowing the base to collapse once moisture gets involved.

-

Weak or missing edge restraint, letting pavers spread or sink.

When those issues are present, pavers lose their advantage.

Do Permeable Pavers Work in Clay Soil?

Yes, but they don’t work the way many people expect. Permeable pavers don’t make clay drain faster.

Clay limits infiltration, so water doesn’t disappear straight down. Instead, permeable systems store water temporarily in the base and release it slowly. That reduces surface runoff and erosion when the system is designed correctly.

This approach is supported by manufacturer technical guides and stormwater design resources, which show that performance depends on base depth, outlet planning, and site conditions. Without that planning, permeable systems often get blamed for problems they were never designed to solve.

The takeaway is simple. No walkway material is bulletproof in St. Louis. The best-performing walkways use materials that work with clay soil and water, not against them, and rely on proper installation to do the heavy lifting.

What a Walkway Needs to Avoid Failure in St. Louis

This is where most long-lasting walkways separate themselves from the ones that keep needing repairs. In St. Louis, success doesn’t come from premium materials. It comes from getting the system right beneath and around the walkway. When the fundamentals are handled properly, failure stops being the norm.

Subgrade vs Base: Why the Difference Matters

Yes, confusing the subgrade and the base is a common cause of early failure. The subgrade is the native soil already on your property. The base is the engineered layer built to protect the walkway from that soil.

Here’s the diagnostic cue. If a walkway settles unevenly within the first few years, the base was likely treated like leveled dirt instead of a structural layer. Clay soil moves no matter what. The base exists to absorb and distribute that movement so it doesn’t reach the surface.

When the two are treated as the same thing, the walkway ends up riding directly on shifting ground.

Base Depth and Compaction: The Non-Negotiables

Yes, shallow or poorly compacted bases are one of the fastest paths to failure. This is where shortcuts show up later.

In real homes, base problems often reveal themselves after heavy rain. Sections feel softer underfoot, low spots form, or settling increases after wet periods. That’s a sign the granular base isn’t deep or dense enough to stay locked together once moisture gets involved.

Two conditions matter most:

-

Adequate base depth to spread loads instead of concentrating them.

-

Proper compaction so the base behaves like a solid mass, not loose fill.

If either is missing, the base collapses gradually, not all at once.

Drainage Design: Where Water Must Exit, Not Just Collect

Yes, effective drainage means water has a planned way out. Letting it soak in place is not drainage.

Homeowners often notice trouble where puddles form after storms or where soil stays damp long after rain stops. Those are signs water is collecting near the base instead of being redirected away. Over time, that repeated saturation weakens the entire system.

Good drainage design creates clear discharge paths. Downspouts are extended, grades are shaped, and runoff is guided away so water never lingers where it can cause damage.

Edge Restraints: The Small Detail That Prevents Big Failures

Yes, missing or weak edge restraint almost always leads to spreading and settlement. It’s one of the easiest problems to overlook and one of the most damaging.

If you see edges dropping, joints widening near the perimeter, or pavers slowly drifting outward, edge restraint is likely failing or missing altogether. Without lateral support, the surface loosens from the outside inward, and water finds new entry points.

Edge restraint doesn’t stop movement entirely. It controls it. Without it, everything else works harder than it should.

-

-

When the base, drainage, and edge restraint are handled as one system tend to hold up better because the surface can flex instead of cracking.

Joint Stability and Maintenance Basics

Yes, joint stability plays a role in keeping the surface intact over time. Joints aren’t just cosmetic lines between units.

When joint sand washes out, small movements start to compound. Homeowners often notice this as slight wobble underfoot or gaps that keep reopening. That’s a sign surface interlock is weakening, even if the base below is still intact.

Simple maintenance like replacing lost joint material helps preserve surface stability. It won’t fix a bad base, but it can prevent small issues from turning into larger ones.

If there’s one thing to remember in St. Louis, it’s that walkways don’t fail because the surface is unlucky. They fail because the base, drainage, slope, and edge restraint weren’t treated like one system. When those pieces are designed for clay movement and repeated moisture, the surface stops drifting, cracking, and settling every season. That’s why homeowners who look at the full approach to professionally built walkways and pathways, not just the surface material, tend to get results that actually last.

DIY Checks Homeowners Can Do Before Repair or Replacement

Before spending money on repairs or committing to a full replacement, it helps to get clear on what’s actually happening. These quick checks won’t diagnose everything, but they will tell you whether the problem is surface-level or structural. That alone can save you from repeating the same fix twice.

Check Where Water Goes During and After Rain

Yes, water movement is the fastest way to identify the real problem. Watch the walkway during a heavy rain or walk it as soon as the storm passes.

If water runs along the path, pools near edges, or keeps the soil damp hours later, drainage is working against you. Pay close attention to downspouts, low spots, and areas where water crosses the walkway. If damage looks worse after storms, water is affecting the base, not just the surface.

A simple rule: if water has nowhere obvious to leave, it’s soaking in below.

Look for Seasonal Movement, Not Just Damage

Yes, timing tells you more than the crack itself. When changes happen matters.

If sections lift in winter and settle back in spring, freeze–thaw and trapped moisture are involved. If gaps open during dry spells and tighten after rain, clay soil is moving underneath. Damage that follows seasonal patterns almost always points to soil and moisture, not wear and tear.

If the walkway behaves differently throughout the year, the ground beneath it is shifting.

Test the Edges and Surface Stability

Yes, edge movement is an early warning sign you shouldn’t ignore. It often shows up before the center fails.

Step gently along the edges and corners. If sections rock, shift, or feel unsupported under light pressure, the base or edge restraint is compromised. On paver walkways, widening joints near the perimeter usually appear before larger settlement occurs.

If the edges move easily, the system is already losing stability.

Identify Repeat Problem Areas

Yes, repeat failures mean the original cause was never fixed. Location matters as much as appearance.

Look for spots that have been patched before or areas where sinking, cracking, or washouts keep returning. If repairs fail in the same place, the surface material isn’t the issue. Something underneath is still active.

Repeated problems are a clear signal that cosmetic fixes won’t hold.

Decide Whether Repair or Replacement Makes Sense

Yes, you can usually tell which direction you’re headed. The pattern of damage makes the call clearer than most people expect.

If the issue is isolated, doesn’t change seasonally, and the surface feels solid elsewhere, repair may be reasonable. If movement keeps coming back, worsens after rain, or shows up across multiple areas, repairs are unlikely to last. That’s when deeper reconstruction or replacement becomes the smarter option.

Running these checks gives you clarity before you call anyone. When you know whether water, soil movement, or both are involved, you’re far less likely to waste money fixing the wrong thing.

Repair vs Replace: What Actually Makes Sense in St. Louis

This decision trips up a lot of homeowners because the walkway usually isn’t completely destroyed. It’s just failing enough to be annoying. In St. Louis, the right call isn’t about how bad it looks today. It’s about whether the system underneath is still doing its job.

When Repair Is Actually Worth It

Yes, repair can make sense when the problem is isolated and stable. The key word is stable.

Repairs tend to hold when the damage is limited to one area, hasn’t spread, and doesn’t change much with the seasons. That usually means the base beneath the walkway is still intact and water isn’t actively working against it. A single low spot, a few shifted pavers, or minor edge movement that hasn’t worsened over time can often be corrected without rebuilding everything.

Here’s the practical test. If the issue looks the same now as it did a year ago and doesn’t get worse after rain or winter, repair has a real chance of lasting.

When Replacement Is the Smarter Call

Yes, replacement is the right move when the foundation is no longer reliable. At that point, surface fixes stop making sense.

If the walkway sinks after rain, lifts in winter, or develops new cracks every year, the base and subgrade are failing together. That’s not something patching can fix. Water exposure, clay movement, or both have already compromised the system.

There’s a clear cutoff most homeowners recognize in hindsight. If you’ve repaired the same spot more than once, or the damage keeps returning despite fixes, replacement isn’t an upgrade. It’s a reset.

Why St. Louis Pushes Decisions Toward Replacement Faster

St. Louis conditions don’t give partial fixes much forgiveness. Clay soil and freeze–thaw cycles keep applying pressure until weaknesses give way.

Once water reaches a compromised base, every wet season weakens it further. Every winter freeze expands the damage. That’s why walkways here often reach a point where repairs feel endless. The environment keeps undoing them.

Replacement works because it allows the system to be rebuilt correctly. The base can be engineered, drainage can be redirected, and grading can be corrected all at once.

How to Decide Without Guessing

Yes, you can usually make the call with a few hard questions. No overthinking required.

Ask yourself:

-

Has the problem spread or changed over time?

-

Does it get worse after rain or winter?

-

Have repairs already failed in the same locations?

If the answer is yes to more than one, repair is unlikely to hold. If the damage is limited, stable, and not tied to weather patterns, repair may be reasonable.

In St. Louis, the smartest choice isn’t the cheapest fix today. It’s the option that stops the cycle of rework and actually holds up to the soil, water, and seasons you’re dealing with.

St. Louis Walkway Planning Checklist (Before Installation)

Before any walkway gets installed, there are a handful of decisions that quietly determine whether it holds up or fails early. In St. Louis, skipping even one of these steps usually shows up later as settling, cracking, or washouts. This checklist is meant to slow the process down just enough to avoid those problems.

Use This Checklist Before You Build

These aren’t design preferences. They’re system requirements for St. Louis soil and weather.

-

Clay soil conditions were assumed from the start

The plan treats native clay soil as expansive and unstable, not as a reliable base. An engineered base is specified to separate the walkway from seasonal soil movement. -

A defined water exit path exists

Runoff from downspouts, driveways, and slopes is directed away from the walkway. Water is not allowed to cross, pool on, or soak into the base. -

Base depth is designed for STL conditions, not minimum specs

The base thickness and material account for heavy spring rain and freeze–thaw cycles. Thin bases or standard details are not being used as shortcuts. -

Compaction method is clearly defined

The plan specifies how the base will be compacted and in lifts, not just that it will be compacted. Poor compaction is one of the most common failure points in local walkways. -

Slope and grading are intentional, not assumed

The walkway has positive drainage and avoids channeling water along its length. Transitions at driveways, steps, and patios are graded to prevent water collection. -

Edge restraints are part of the structure, not an afterthought

The design includes rigid edge restraint to prevent lateral movement. Edges are treated as load-bearing components, not decorative trim. -

Joint stability and surface protection are planned

Joint material is specified to resist washout and movement. The surface system is designed to stay locked together during wet and cold seasons.

Final Check Before Installation

If even one of these items is missing or unclear, the walkway is being built with risk baked in. In St. Louis, failures don’t usually come from bad materials. They come from incomplete planning.

A walkway that checks every box here usually performs quietly for years. One that doesn’t will start asking for repairs much sooner than expected.

Questions St. Louis Homeowners Ask About Failing Walkways

Homeowners usually arrive at this point with a few very specific questions. They’ve seen the damage, they’ve heard conflicting advice, and they want straight answers without the sales spin. These are the questions that come up most often in St. Louis homes, especially after a few seasons of frustration.

Is Walkway Failure Just Normal in St. Louis?

No, failure isn’t inevitable, but poor planning makes it common.

St. Louis clay soil, heavy rain, and freeze–thaw cycles are tough on walkways, but they don’t automatically doom them. Walkways fail here when soil movement, water management, and base design aren’t addressed together. When those factors are handled correctly, walkways can perform for decades without major issues.

Why Did My Walkway Look Fine for a Year or Two Before Failing?

Yes, delayed failure is typical with clay soil and water problems.

Expansive clay often takes time to show its effects. The first year may pass without obvious damage, especially if rainfall patterns are mild. Once the soil cycles through wet springs, dry summers, and freezing winters, movement builds and the surface starts reacting. That delay doesn’t mean the installation was fine. It usually means the failure was already in motion underground.

Can I Just Re-Level or Patch Instead of Rebuilding?

Sometimes, but only if the base is still stable.

If settling is minor, hasn’t spread, and doesn’t worsen after rain or winter, repair may hold. If the same areas keep moving, patching won’t stop it. Re-leveling surface material without fixing drainage or base issues just resets the clock. In St. Louis, repeated repairs are usually a sign that replacement is the smarter long-term move.

Why Does My Walkway Get Worse After Heavy Rain?

Because water weakens the base and activates clay soil movement.

Rain doesn’t just affect the surface. It saturates the soil underneath, softens the base, and increases pressure when the ground expands. If water has no clear exit path, it stays trapped below the walkway. That’s when sinking, washouts, or winter heaving start to accelerate.

Is Concrete or Pavers Better for St. Louis Walkways?

Pavers generally tolerate movement better, but installation matters more than material.

Concrete is rigid and depends heavily on a stable subgrade. When clay soil moves, concrete tends to crack. Pavers are modular and can flex slightly, which helps them handle minor soil movement. That said, pavers will still fail if the base is thin, poorly compacted, or exposed to water. Material choice helps, but it doesn’t override system design.

How Long Should a Properly Built Walkway Last Here?

A well-installed walkway should last decades, not just a few years.

When the base is engineered, drainage is controlled, and edges are restrained, walkways can hold up through repeated freeze–thaw cycles and heavy rain. Premature failure usually points to shortcuts, not age. If a walkway starts failing within five to seven years, something underneath wasn’t built to handle local conditions.

How Do I Know If a Contractor Is Cutting Corners?

Look for vague answers about base depth, drainage, and soil.

If an installer can’t clearly explain how they manage clay soil, where water will go, or how the base is built and compacted, that’s a warning sign. Good contractors talk about systems. Shortcut plans focus on surface materials and aesthetics.

What’s the Biggest Mistake Homeowners Make With Walkways?

Assuming the surface material is the most important decision.

In St. Louis, the ground matters more than what you see on top. Most failures come from what’s underneath the walkway, not what it’s made of. When homeowners understand that early, they avoid chasing repairs and get better long-term results.

What to Do Next to Build a Walkway That Actually Lasts in St. Louis

If there’s one takeaway that matters most, it’s this. Walkway problems in St. Louis are rarely about the surface you see. They’re about what’s happening underneath and how water and clay soil are interacting with the system over time.

Clay soil moves. Water looks for the easiest path. Freeze–thaw cycles keep applying pressure year after year. When a walkway isn’t planned and built with those forces in mind, failure isn’t random. It’s predictable. That’s why repairs often feel temporary and why some walkways seem to fall apart no matter what material was used.

The good news is that failure isn’t inevitable. When the base is engineered instead of improvised, drainage has a clear exit, slopes are intentional, and edges are restrained, walkways in this region can perform quietly for decades. No seasonal surprises. No recurring fixes.

If you’re trying to decide whether to repair, replace, or start fresh, focus on systems, not symptoms. Look at where water goes. Watch how the walkway behaves after rain and through winter. Those clues tell you far more than surface cracks ever will.

For homeowners who want a deeper look at how these systems are planned and built locally, the team at Retaining Wall & Paving Solutions shares practical guidance rooted in real St. Louis conditions on their homepage at https://rwpsllc.com/. It’s a useful next step if you want to understand what a long-lasting walkway actually requires before making a decision.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s building something that works with the soil, the weather, and the reality of this region, instead of fighting it every season.